Does early depressive mood expire following radical retropubic prostatectomy in patients with localized prostate cancer?

Article information

Abstract

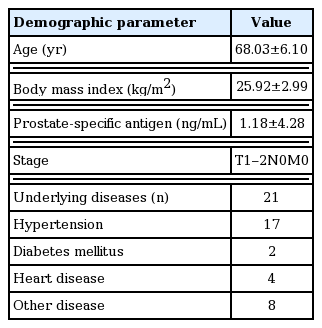

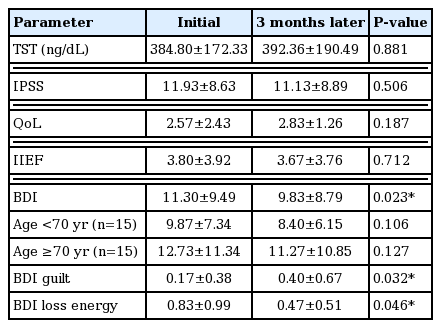

In this study, the pattern of depressive mood in patients following radical prostatectomy (RP) for localized prostate cancer (PCa) was determined. A total of 30 patients (aged 68.03±6.1 years) who were diagnosed with localized PCa and underwent RP within 1 month entered the study. Evaluations included body mass index, prostate-specific antigen, testosterone, underlying disease, international prostate symptom score and quality of life (QoL), international index of erectile function as well as Beck depression inventory (BDI), both at the initial stage and 3 months later. Basic demographic data, laboratory results, and questionnaires were analyzed statistically. The BDI score significantly decreased 3 months after the surgery. In correlation analysis, BDI was related with the international prostate symptom score but not with the underlying disease, QoL or international index of erectile function. Body mass index was identified as one of the risk factors to decrease the probability of BDI score (≥3) significantly. Underlying disease increased the probability of BDI score. In the assessment of the correlation between BDI and each subscale, sadness, self-dislike, self-criticalness, and worth-lessness showed high correlation. In the early period, depressive mood was improved at the short-term follow-up in localized PCa patients after RP. Voiding symptoms were only related with the depressive mood, but not with other parameters, including sexual function. The depressive mood had no effect on the QoL in the early stage.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer patients are prone to depression, with a 22%–29% median prevalence rate (Raison and Miller, 2003). Intuitionally, many factors like fear of cancer, economic burden, treatment-related physical and psychotic burden, and functional deterioration might have an effect on patients’ depression. Considering the fact that one of the cancers with the highest incidence in men around the world is the prostate cancer (PCa), research regarding the relationship between PCa and depression is far-reaching. Like other malignancies, it has been known that PCa is related with depression (Derogatis et al., 1983; Roth et al., 1998). A previous report found that almost 30% of PCa patients met general distress status in the clinical field (Carlson et al., 2004). However, the main research interest concerning depression in PCa patients is usually related to advanced PCa with androgen deprivation treatment (ADT) because many studies have suggested that there is a positive association between ADT and depressive mood (Dinh et al., 2016; Nead et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2018).

Localized PCa has a high success rate of treatment and 5-year survival rate (Walz et al., 2007), and there are some reports that early localized PCa patients have a low level of psychopathology (Bisson et al., 2002), therefore the interest regarding the psychopathologic effect in this population has been relatively low. However, recently contradictory research has been published stating that newly diagnosed PCa is associated with psychotic distress and also increased the risk of suicide by 2.5 times within 1 year of diagnosis, compared to the general population (Fang et al., 2012), and persistently elevated the risk thereafter (Fang et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2009). At the same time the interest in the quality of life (QoL) has elevated, generating a recent increase in the necessity for research regarding the relationship between localized PCa and depression. Furthermore, although the most common treatment for localized PCa is radical prostatectomy (RP), the fact is, little is known about the relationship between RP for PCa and emotional stress, including depression (Wilt et al., 2009). Accordingly, psychopathological status is less frequently treated than systemic and physical pathologic status (Kurtz et al., 2001). Understanding the relationship between depressive mood and PCa is essential for providing proper treatment and support for PCa patients because some studies have suggested that depression is related with QoL as well as with the cancer survival rate (Jayadevappa et al., 2012; Satin et al., 2009).

Some potential factors known to have an effect on depression in patients with localized PCa after RP include age, obesity, cancer stage, serum testosterone, underlying disease, lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), sexual function, and QoL (Nelson et al., 2011; Tavlarides et al., 2013; van den Beuken-van Everdingen et al., 2009). Likewise, with the relationship between PCa and depressive mood, there is a shortage of studies exploring factors influencing depressive mood in PCa patients and patterns in that relationship.

The study objective is to determine the pattern of depressive mood in patients who underwent RP for localized PCa and the diverse factors that may affect depressive mood in the early period after the surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

This present study was performed with a total of 30 patients who were newly diagnosed with localized PCa and underwent RP in our hospital. The principles of the Helsinki Declaration were followed in lieu of formal ethics committee approval and all study processes were approved by the Gachon University Institutional Review Board (approval number: GCIRB 2017-296).

The study period was from September 2017 to August 2018, including a total of 30 patients (aged 68.03±6.1 years) who were diagnosed with localized PCa and underwent RP within 1 month of diagnosis. All of the patients had no history of psychopathological disease including depression. The participation in this study was voluntary and all the patients submitted informed consent. Evaluations included body mass index (BMI), initial serum prostate specific antigen, serum testosterone, and assessment for the underlying disease.

Functional measurement

Three questionnaires were used to assess the study parameters: (a) the International Prostatic Symptom Score (IPSS) & QoL, (b) the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), and (c) Beck depression inventory (BDI). IPSS and QoL is a questionnaire used to evaluate LUTS and QoL which shows both compatibility and reliability (Boyle, 1997). IIEF is a widely used multi-dimensional self-reported questionnaire for the evaluation of male sexual function and has been regarded as the gold-standard treatment outcome measurement for erectile dysfunction (Rosen et al., 2002). BDI is widely used self-reported questionnaire that evaluates the degree of depressive symptoms and it has been proven to have both reliability and sensitivity (Pop-Jordanova, 2017).

IPSS, QoL, IIEF, and BDI were assessed twice, within 1 month after RP and again 3 months later. All questionnaires were answered using a self-recorded method under the assistance of a trained nurse.

Statistical analysis

Basic demographic data, laboratory results, and questionnaire data were analyzed statistically. The comparison of parameters between initial assessment and follow-up assessment was evaluated using paired t-tests. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of distribution of continuous variables. Correlation between BDI score and other variables such as age, BMI, testosterone level, IPSS, QoL, IIEF and underlying disease was evaluated using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Inter-scale correlation between BDI and each subscale for evaluation of the degree of correlation was also verified using the Pearson correlation coefficient. To assess a possible predictive value of variables on the change of depressive mood (≥3), logistic regression analysis was performed using the initial BDI score as the dependent variable, with age, BMI, testosterone level, initial IPSS, initial QoL, initial IIEF, and underlying disease used as the independent variables. The data are presented with mean±standard deviation and all tests were considered significant two-sided with P<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

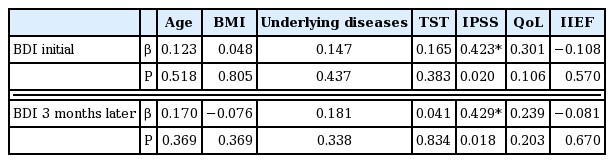

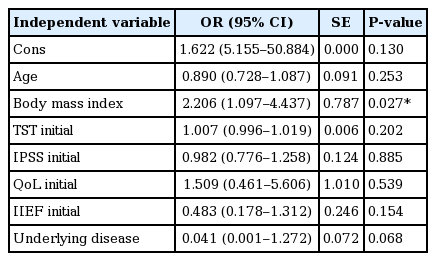

RESULTS

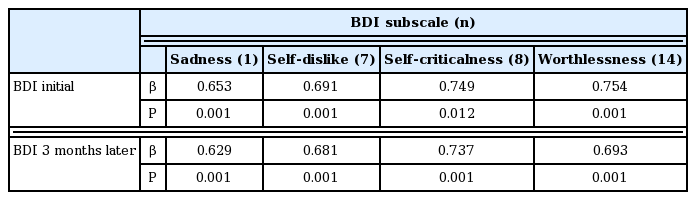

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. BDI level significantly decreased 3 months later, but other parameters such as testosterone, IPSS, QoL, and IIEF were not significantly different (Table 2). When the target patients were divided into an older and a younger group (age ≥70 and age <70 years), no change in BDI between initial assessment and assessment 3 months later was detected in both groups (Table 2). BDI scores were related with IPSS in both initial and 3 months later (r=0.423, 0.429, P< 0.05) (Fig. 1), however, in terms of age, BMI, underlying disease, QoL, and IIEF, there was no significant correlation (P>0.05) with BDI score in either the initial assessment or 3 months later (Table 3). BMI was identified as one of the risk factors to significantly decrease the probability of BDI score (≥3) (odds ratio [OR], 2.206; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.097–4.437; P=0.027). The underlying disease showed a borderline P-value for association with BDI score (OR, 0.041; 95% CI, 0.001–1.272; P=0.068) and there was no significant correlation detected between decreasing BDI score (≥3) with age, testosterone, IPSS, QoL, and IIEF (Table 4). In correlation analysis between BDI and each BDI subscale, sadness, self-dislike, self-criticalness, and worthlessness showed high correlation (r>0.6, P<0.05); this could possibly imply that these subscales are highly affected with BDI (Table 5) (Supplementary Table 1).

Association between Beck depression inventory (BDI) and international prostatic symptom score. CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

Correlation between PCa and psychopathologic status has recently been recognized; accordingly, research regarding depressive mood in PCa patients is essential, not only because of the relationship between depressive mood and patients’ QoL, but also because there are some reports that depression is a meaningful predictor of survivor and mortality in PCa patients (Jayadevappa et al., 2012; Satin et al., 2009). Risk factors for emotional stress extend beyond the cancer diagnosis itself and include surgery-related psychotic and physical burdens and functional deterioration after surgery. For example, sexual change and LUTS are risk factors for depressive symptoms (Jayadevappa et al., 2012). Occasionally, a higher degree of depressive symptoms at the time of diagnosis but prior to treatment may have an influence on sexual and urinary dysfunction, with the reverse association also applying (Mohamed et al., 2012). As a result of all of the above factors, the importance of depressive mood in patients with PCa is expanding.

There are some reports about the relationship between depressive mood and functional deterioration (Jeong et al., 2015; Korfage et al., 2006; Ravi et al., 2014; Rosen et al., 2002; Tavlarides et al., 2013). Definitively, patients with severe LUTS are at a high risk of depression with increasing severity of LUTS worsening depression (Jeong et al., 2015), and higher levels of cancer-specific anxiety are related to poor sexual function (Tavlarides et al., 2013). However, functional impairments do not seem to be the only reason depressive symptoms occur. Ravi et al. (2014) reported that despite a PCa diagnosis, and functional impairment being risk factors for mental health issues (anxiety, depressive disorder, and suicide), patients treated with RP or radiation therapy had a lower risk of developing mental health issues compared with patients undergoing watchful waiting who probably have better urinary and sexual function. So there is a need for research regarding the factors that affect depressive mood and the degree of the importance of these factors.

Another prospective study assessed anxiety and depression after a PCa diagnosis and treatment from 6-month to 5-year follow-up showed a significant and clinically meaningful improvement in mental health at 6-month follow-up (Korfage et al., 2006). The findings from this study are consistent with our findings, which showed some improvement in depressive mood 3 months after RP. From this result, it might be interpreted that the nature and cause of depressive mood of PCa patients are different in the early and the late period of treatment. Considering this, our finding raises several points for correlation and discussion with regards to research findings, which might give some clue about the characteristics of depressive mood in the early period. Each item of BDI can be summarized by its characteristics (Lötsch et al., 2018). In PCa patients, feelings such as sadness, self-dislike, self-criticalness, and worthlessness could have more effect on their depressive mood (Supplementary Table 1).

There are some interesting points in which this research is different from the other studies. First, considering other reports that sexual dysfunction, urinary dysfunction, and resulting bother increased significantly over 6 months among all patients, particularly ones treated with surgery, our results that only LUTS was related to the depressive mood in the early period is quite interesting (Monahan et al., 2007). It shows that during the early period of treatment, PCa patients have minimal expectation related to sexual function. On the contrary, the presence of urinary symptoms was directly related to the depressive symptoms. Secondly, until now, many researchers have been interested in the relationship between QoL and PCa. Some studies have even recommended regular measurement of QoL as an independent prognostic factor for PCa (Weeks, 1992). Sexual change has been linked to the increased risk of depressive symptoms and poor QoL in studies with a longer follow-up (Gore et al., 2009; Litwin et al., 2001). However, in the present study, there was no relationship found between lower urinary function, sexual function, depressive mood, and QoL. Another interesting finding is that functional deteriorations are not the major factor that determines the QoL in patients in the early stage after RP in localized PCa. Thirdly, in contrast with a report that younger age (<70 years) was predictive of poorer psychopathology (Bisson et al., 2002), our report shows no difference in relation between BDI and IPSS score according to age. One possible explanation is because our study was performed within an exceptionally short period following prostatectomy compared to others. Finally, obesity was identified as a related factor that decreased depressive mood (BDI score decrease≥3), but the existence of underlying disease might also increase depressive mood.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is about the earliest tendency of changing depressive mood in PCa patients and the affecting factors but has some limitations including a short study duration and a small sample size. In terms of small sample size, the largest significant correlation in our paper is 0.429, which is slightly below the large effect of 0.50, only 30 of sample size can give us almost 0.80 of power at the 0.05 level (Cohen, 1992). However, further studies are required in order to establish a sound scientific basis for the determination of depressive mood in PCa patients.

Depressive mood improved significantly at the short-term follow up in patients with localized PCa after RP. Voiding symptoms were mainly related to the depressive mood; however sexual function and QoL had minimal impact on the depressive mood in the early stage. These relationships should be followed up for a longer period to ascertain the change in the pattern which could provide a better chance to support patients’ emotional wellbeing and provide long-term care.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Alvogen Pharmaceuticals.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material can be found via https://doi.org/10.12965/jer.1938160.080.

Beck depression inventory (BDI) subscales according to their characteristics