INTRODUCTION

Adolescence is a time of dramatic change and rapid growth in the life (Johnson et al., 2009; Spear, 2002). These growth and development from adolescence drive many aspects of biological processes, which can be characterized by behavioral, hormonal and neurochemical changes (López-Arnau et al., 2015; Steinberg, 2005). Experiences of adolescence can be exerted positive and negative effects on brain development. Evidence from animal studies suggests that environmental factors in adolescent rats can influences cognitive function (Comeau et al., 2015; Shao et al., 2013).

Physical exercise has a positive effect on brain function, which is characterized by improving memory function and increased neural plasticity (Cotman and Engesser-Cesar, 2002; Jin et al., 2008). Many previous studies have shown that physical exercise may contribute to cognitive improvement in the aging brain by preserving adult neurogenesis (Winocur et al., 2014; Yau et al., 2014). Enhanced of neurogenesis is implicated in the improvement of memory function and enhances neuronal plasticity (Lledo et al., 2006). Exercise is known to improve cognitive function and ameliorates neurological impairment following various brain injuries such as cerebral ischemia, Alzheimer, and Parkinson diseases (Lee et al., 2014; Seo et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2007). Several animal studies have provided strong evidence to suggest that physical exercise-induced cognitive improvement has been correlated with a protection of age-related hippocampal damage.

High fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity has a negative effect on brain function, which is characterized by insulin resistance and adipose tissue inflammation and reduced memory ability (Cho et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2016; Norris et al., 2016). It has been associated with increased risk of several diseases including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, prostate cancer, dementia, and Alzheimer disease (Balistreri et al., 2010). Many previous studies have shown that overweight or obesity is associated with decrease of cognitive function (Baxendale et al., 2015; Lennox et al., 2015). Cognitive performance in adult patients is affected by insulin resistance, steady-state plasma glucose levels, and body mass index (Fukushima et al., 2016). HFD-induced obesity impairs structure and functions of hippocampus in mice (Medic et al., 2016; Park et al., 2010).

Although the positive effect of exercise and negative effect of obesity on cognitive function have been documented, it has not been well whether comparison of both effects of exercise and obesity on cognitive function in adolescent rats. In the present study, we evaluated the behavioral changes related to cognitive function induced by exercise and obesity in adolescent rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and housing conditions

Male Wistar rats (80±10 g, 4 weeks old) were used in this study. All animal experimental procedures conformed to the regulations stipulated by the National Institutes of Health and the guidelines of the Korean Academy of Medical Science. This study was approved by the Kyung Hee University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Seoul, Korea) (KHUASP [SE]-15-082). The mice were housed under controlled temperature (20°C±2°C) and lighting (07:00 a.m. to 19:00 p.m.) conditions with food and water available ad libitum. The rats were randomly divided into three groups: the control group (CON, n=10), the exercise group (Ex, n=16), the high fat diet group (HFD, n=16). The HFD containing fat 60% was freely provided.

Treadmill exercise protocol

The rats in the exercise group were made to run on a treadmill for 30 min once a day for 8 weeks starting 4 weeks after birth, according to the previously described method (Kim et al., 2004). The treadmill exercise load consisted of running at 2 m/min for the first of 5 min, at 3 m/min for the next 5 min, and then at 5 m/min for the last 20 min at 0 degree of inclination. The rats in the CON and HFD groups were left in treadmill without running for the same period as the exercise group.

Morris water maze test

Morris water maze test In order to evaluate the spatial learning ability in rats, the latency in the Morris water maze test was determined, as the previously described method (Heo et al., 2014). The Morris water maze consisted of a circular pool (painted white, 200-cm diameter, 35-cm height), filled with water (22°C±2°C) made opaque addition 1 kg of skim milk powder. A platform (15-cm diameter, 35-cm height) submersed 2 cm below the water surface in one of four quadrants in the pool. There were several visual cues on the walls of the room. A video-recorder was hanged from the ceiling and was connected to a tracking device (S-MART: Pan-Lab, Barcelona, Spain). The animals were subjected to three trials per session. For each trial, the rat was placed in the water, facing the wall of the tank, in one of the three start locations. The rat was allowed to search for the platform for 60 sec. If the rat found the platform, remaining on the platform for 10 sec was permitted. If the rat did not find the platform within 60 sec, the rat was guided and allowed to remain on the platform for 10 sec. The latency times to find the submerged platform were recorded. The animals were tested in this way for 4 days.

Step-down avoidance test

In order to evaluate short-term memory in the rats, the latency in the step-down avoidance test was determined, as the previously described method (Shin et al., 2016). The rats were trained in a step-down avoidance test on the 7 weeks. The rats were positioned on a 7×25-cm platform with a height of 2.5 cm, and then allowed to rest on the platform for 2 min. The platform faced a 42× 25-cm grid of parallel 0.1-cm caliber stainless steel bars, which were spaced 1 cm apart. In the training sessions, the animals received 0.3-mA scramble foot shock for 2 sec immediately upon stepping down. After 24 hr, retention time was assessed. The interval of rats stepping down and placing all four paws on the grid was defined as the latency time. The latency over 300 sec was counted as 300 sec.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Duncan post hoc test. Differences between groups were considered significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

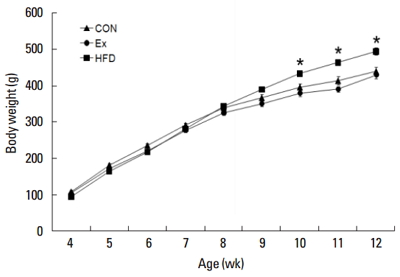

Effects of exercise and obesity on body weight

The body weight was significantly increased to 434.75±7.57 g in HFD group after 6 weeks of the high fat diet as compared to 397.43±9.78 g in the CON group after a regular diet. The body weight was significantly increased to 465.50±8.67 g in the HFD group after 7 weeks of the high fat diet as compared to 415.14± 10.97 g in CON group after a regular diet. The body weight was significantly increased to 496.50±9.54 g in the HFD group after 8 weeks of the high fat diet as compared to 441.14±11.87 g in the CON group after a regular diet (P<0.05). In contrast, the Ex group did not show significant effect following treadmill exercise as compared to the CON group (Fig. 1).

Effects of exercise and obesity on spatial learning ability in the Morris water maze test

Spatial learning ability was measured using the Morris water maze test (Fig. 2). The escape latency time (in seconds) is demonstrated for the 4 days of reference memory testing. The escape latency (sec) of the 4-day trial was significantly increased to 42.56±2.63 sec in the HFD group as compared to 28.13±3.86 sec in the CON group (P<0.05). In contrast, the Ex group did not show significant effect following treadmill exercise as compared to the CON group.

Effects of exercise and obesity on short-term memory in step-down avoidance test

Short-term memory was measured using the step-down avoidance test (Fig. 3). The latency time (sec) was significantly decreased to 87.63±16.47 sec in the HFD group as compared to 198.30±38.06 sec in the CON group (P<0.05). In contrast, the Ex group (199.30±27.48 sec) did not show significant effect following treadmill exercise as compared to the CON group.

DISCUSSION

Physical exercise improves cognitive function, hippocampal neurogenesis, neural plasticity induce by neurotrophic factors (Altmann et al., 2016; Baek, 2016; Sim et al., 2004). Most prior studies have demonstrated the effects of exercise on cognitive impairment induced by several diseases (Baek, 2016; Ma et al., 2017). HFD-induced obesity model was used to indicate cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety (Abildgaard et al., 2011; Kaczmarczyk et al., 2013). In the present study, we evaluated the effects of exercise and obesity on cognitive function in adolescent rats. As previously mentioned, adolescence is a critical period for stabilization of neural circuit, neuronal plasticity, and intellectually and emotionally improvement. In present study demonstrated the effects of exercise and obesity on cognitive function in adolescent rats.

A recent study showed that treadmill exercise in normal adolescent miceimproves short-term memory in the Y-maze test. Also, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and tyrosine kinase B (TrkB) expression and cell proliferation in normal adolescent mice were increased after treadmill exercise for 12 weeks (Kim et al., 2016). Increased expression of hippocampal BDNF and enhanced cell proliferation caused by treadmill exercise might facilitate neuroplasticity in mice (Ma et al., 2017; Seo et al., 2014). The present results showed that treadmill exercise was similar level of control group on spatial learning ability and short-term memory. Consistent with our study, the several reports have demonstrated that the sham+Ex group exerted no significant effect on the number of error choice in the radial 8-arm maze test as compared to the sham group. However, treadmill exercise enhanced BDNF and TrkB expressions in the hippocampus of rats (Sim, 2014). Many studies have shown that treadmill exercise in young normal animals exerted no significant effect on spatial learning and memory and short-term memory in the radial 8-arm maze and step-down avoidance tests (Heo et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2010). In the light of these results demonstrate that treadmill exercise in normal young animals may be exerted no significant effect on cognitive function as compared to the control group.

The HFD-induced obesity is considered to reduce neuronal plasticity and cognitive function in the brain (Murray et al., 2009; Woo et al., 2013). HFD is associated with reduced BDNF and reduced performance on an active avoidance test (Noble et al., 2014). A recent study showed that cognitive function was impaired in the HFD-induced obese mice (Kim et al., 2016). However, HFD initiated in adolescent but not adult mice impaired memory ability in the water maze test (Klein et al., 2016). The present results showed that spatial learning ability and short-term memory was significantly decreased HFD-induced obesity group as compared to the control group. Consistent with our study, the majority of reports have demonstrated that HFD-induced obese mice were reduced the number of neurons in the hippocampus. These results indicate that HFD-induced obesity in normal animals can be caused by cognitive impairment.

These results suggest that positive effect of physical exercise in adolescence rats may be exerted no significant effect on cognitive function. But, negative effect of HFD-induced obesity might induce cognitive impairment. HFD-induced obesity in adolescent rats may be used as an animal model of neurodevelopmental disorders.